After World War II, the rupture within the victorious Allied camp quickly led to the establishment of a bipolar global order. This new alignment saw the emergence of two dominant ideologies: on one side, the capitalist system, led by the United States, advocating free markets and political democracy; and on the other, the Soviet Union, promoting socialism under the banner of the dictatorship of the proletariat and the Communist International. These two systems justified their rivalry with a binary worldview, categorizing the world in terms of absolute “good” versus “evil.” Within this framework, both the U.S. and the USSR felt obligated to support any opposition to their rival, regardless of the nature, goals, or methods of these factions. However, their ultimate aim was to assert complete dominance over the global stage and defeat the opposing camp. This ideological division consequently restructured the world into three primary categories: the First World, consisting of countries aligned with the U.S.; the Second World, comprising nations allied with the Soviet Union; and the Third World, made up of countries that remained unaligned with either bloc.

The term “Third World” first emerged in French intellectual circles. Initially, it did not refer to underdeveloped countries but rather to nations that did not fit into the prevailing capitalist or socialist systems. Later, the Chinese redefined the term, claiming that the Third World represented the true revolutionary and anti-imperialist world. This notion became the foundation for many liberation and revolutionary movements. As a result, both the United States and the Soviet Union sought to expand their influence in Third World countries. According to this theory, from 1947 until the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in 1991, the United States played a central role in orchestrating over 40 coups around the world. Countries such as Greece, Syria, Cuba, Iran, Albania, Guatemala, Thailand, Laos, Lebanon, Iraq, Congo, Turkey, Ecuador, South Vietnam, the Dominican Republic, Brazil, Bolivia, Indonesia, Zaire, Panama, Ghana, Cambodia, Chile, Uruguay, Argentina, Pakistan, South Korea, Chad, Grenada, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Paraguay, the Philippines, Nicaragua, and El Salvador all fell victim to this geopolitical struggle.

The Geopolitical Landscape of the 1970s

The 1970s were marked by a series of significant and complex events. The culmination of independence movements across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the fragmentation within the socialist camp, and the suppression of popular uprisings in Eastern Europe by the Red Army all weakened the foundations of the bipolar world order. Meanwhile, the success of Castro’s revolution in Cuba and the Vietnam War—coupled with a massive wave of opposition to the war within the United States itself—redefined the geopolitical landscape. New leftist movements began to emerge in the Western world, often independent and distinct, and at times, even opposing the existing global order. From the May 1968 movement in France to the Palestinian liberation struggles, these movements reshaped the political dynamics of the era.

In the Middle East, following their crushing defeat in the Six-Day War, the Arab states began preparing for the Yom Kippur War. At the same time, OPEC, at the height of its influence in the early 1970s, united oil-exporting countries against Israel and raised the price of oil from $3 to $12 per barrel. This price increase, combined with a decline in U.S. oil production, plunged the developed nations into an economic crisis. This was a strange and transformative decade. The Egypt-Israel war, the energy crisis in the Middle East, the Watergate scandal, and the U.S. abandonment of Vietnam all signified a shift. American totalitarianism had evolved, with the U.S. now directly intervening in the governments of Third World countries to maintain economic control. These policies laid the groundwork for the rise of neoliberalism in Latin America. In this context, the military leaders of Uruguay issued a communiqué that set the stage for the military coup of María Bordaberry. Latin America was engulfed by a wave of coups, from Argentina and Brazil to Bolivia, Paraguay, Chile, and Uruguay. The shadow of the Truman Doctrine loomed large, setting much of Latin America ablaze.

Cinema as Political Reflection and Critique

Cinema as Political Reflection and Critique

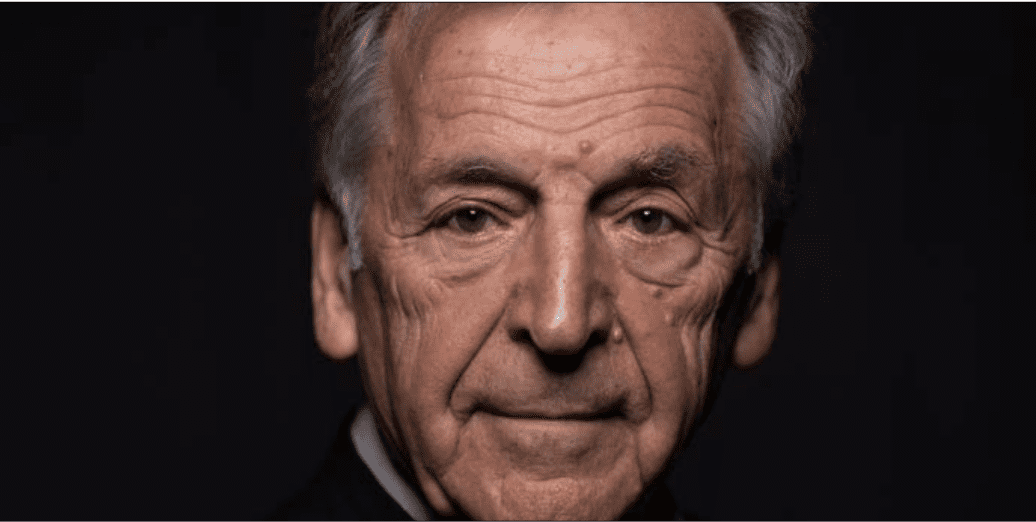

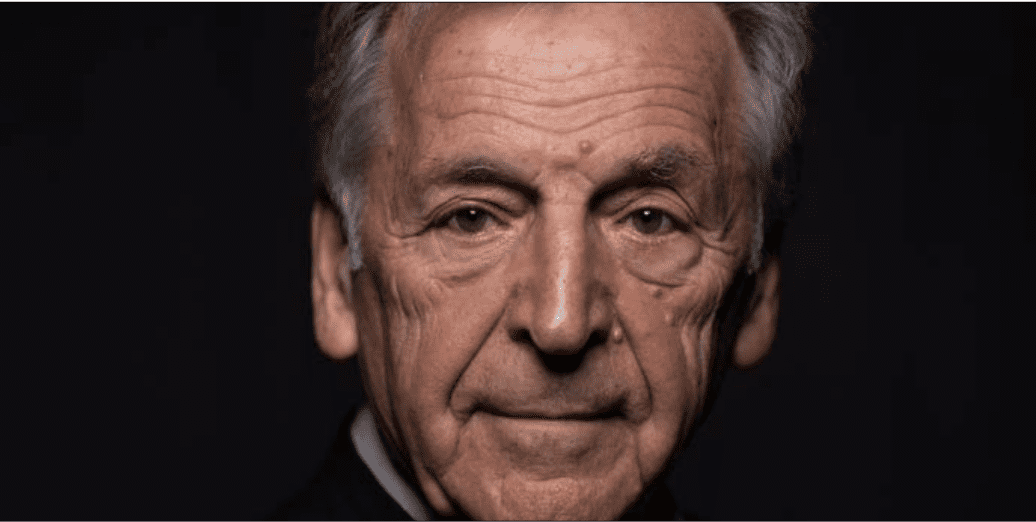

Cinema has always been a medium through which political and social realities are reflected, and some filmmakers have managed to push the boundaries of conventional cinema to critique global events. Costa-Gavras is one such filmmaker. Amid the ideological divide of the East-West conflict, he chose to critique this very worldview, presenting a unique narrative of the world around him. Born into a communist family in Greece, Gavras himself was a victim of the binary perspective of East and West. After the colonels’ coup in Greece, he migrated to France, where he became deeply influenced by the political and social climate of the time. This led to the creation of a trilogy consisting of Z, The Confession, and State of Siege, each of which, in its own way, critiqued global divisions and the policies of the superpowers. Gavras studied literature at the Sorbonne and later pursued film studies at the Institute for Advanced Cinematic Studies. While in Paris, he became involved with a circle of leftist French artists, including Simone Signoret and Yves Montand, who fused politics with art. Though Gavras claims his films primarily explore human relationships, politics and a critical leftist perspective are undeniably central to his work.

State of Siege: A Cinematic Critique of Latin American Politics

State of Siege, filmed in Chile in 1972, depicts the kidnapping of a government official by the Tupamaro guerrillas in Latin America. Although the film does not directly mention Uruguay, the audience unmistakably associates the story with the country. Instead of focusing on a single nation, Gavras examines the issue on a regional scale. Alongside a group of politically engaged artists, Gavras portrayed the conflict between U.S.-backed dictatorships and leftist guerrillas. The film’s direction, combined with Yves Montand’s powerful performance and Mikis Theodorakis’ striking score, created a cinematic-political masterpiece that remains open to analysis even after five decades. Made during the presidency of Salvador Allende in Chile, the film’s production coincided with a critical moment in Latin American history. Just one year after its creation, Chile experienced a military coup that ousted Allende and plunged the country into a dark era.

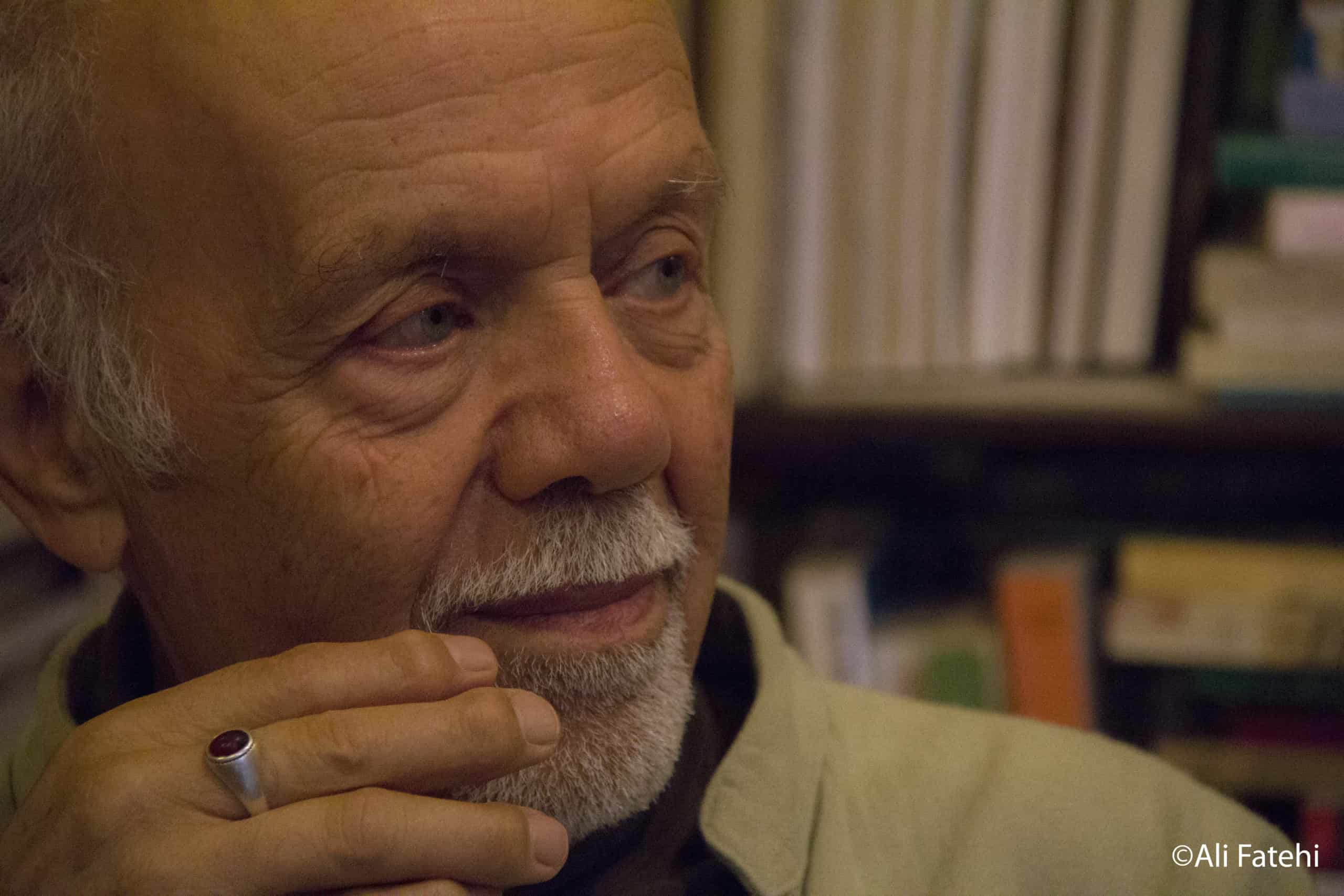

Interview with Ahmad Salamatian on State of Siege

Interview with Ahmad Salamatian on State of Siege

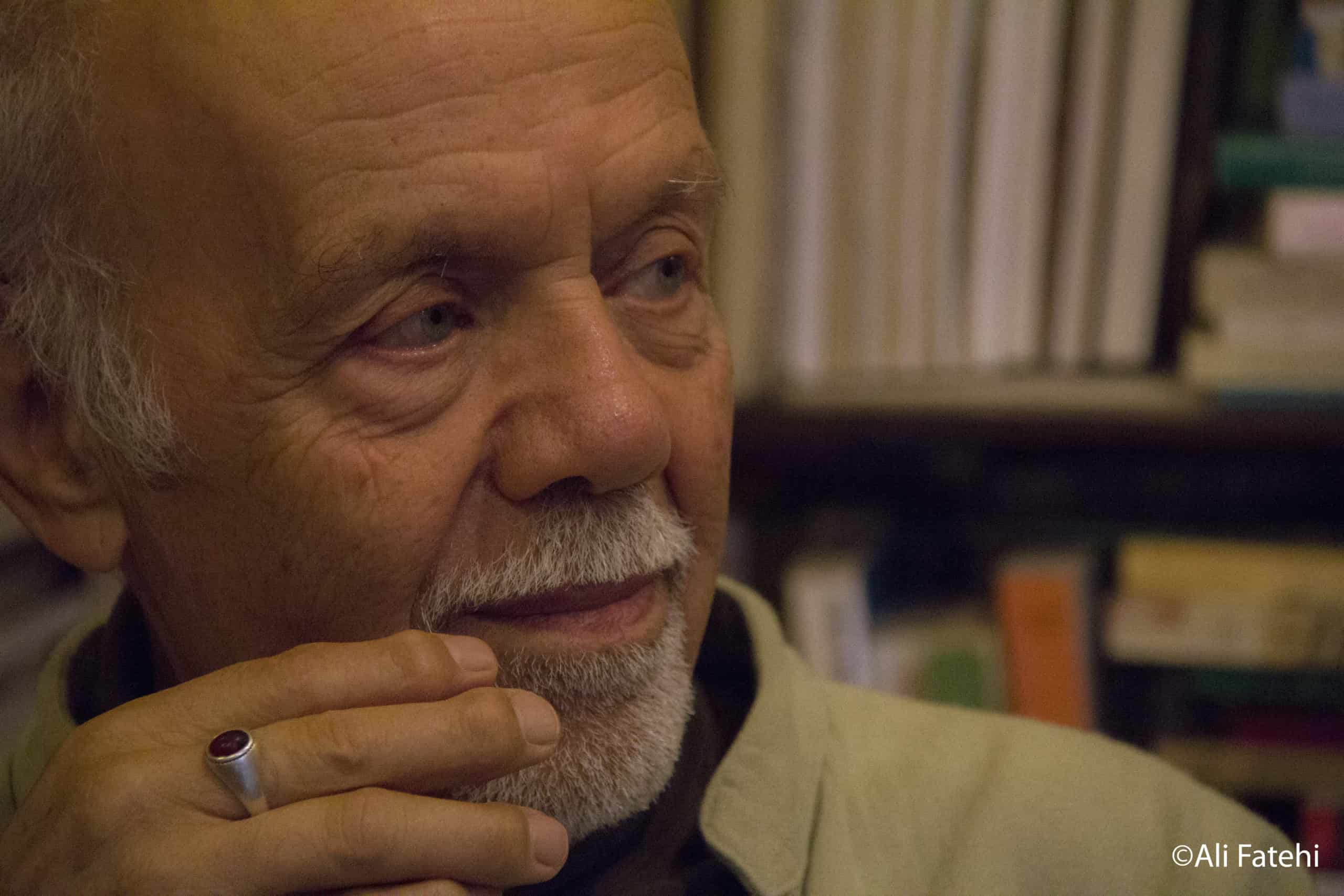

A conversation with Ahmad Salamatian, a political activist and close friend of Costa-Gavras, can shed light on the deeper layers and hidden dimensions of State of Siege. Having firsthand experience in the political and cultural circles of France in the 1970s, Salamatian offers a unique perspective that allows for a more precise analysis of the film’s narrative and its relationship to historical realities. His insights contribute greatly to understanding the film’s connection to the political conditions of its time and the prevailing ideologies.

Fatehi: Mr. Salamatian, you closely experienced the profound political and social transformations of the 1960s and 1970s, and you followed the events in Latin America closely. How do you see State of Siege as a film?

Salamatian: Well, to me, State of Siege should really be viewed alongside Gavras’ previous two films. Why? Because it represents an evolution in his work as a filmmaker. The three films I’m talking about are: first, Z, which is his most famous; second, The Confession, which is the most courageous; and then, finally, State of Siege.

Gavras, who grew up in a communist family, and whose father was an active member of the Greek Communist Party, didn’t find it easy to question the communist system. Just a month before, that very system had once again suppressed dissent in a socialist country—Czechoslovakia—through military intervention. Criticizing this system was a brave act, especially at a time when questioning the socialist camp was uncommon, even in France.

That’s why, despite the overwhelming public reception of The Confession, Gavras faced strong backlash from many communists. Even his closest friends, who had helped shape his artistic journey—like Yves Montand, who starred in the film—engaged in intense debates with him. He was accused of playing into the hands of global capitalism. To make the film, Gavras had to convince his political allies—and he did. I believe it’s this kind of courage that establishes him as a political filmmaker.

For me, a political film isn’t about inventing a central hero for the audience to root for—someone who is either good or bad, virtuous or evil. The definition of a political film isn’t based on presenting a heroic character. What’s more important is how the film analyzes a situation. In State of Siege, it’s not clear if the guerrillas who take a hostage are the heroes or if the CIA officer they kidnap is the villain. All the characters are portrayed as individuals caught in their political and social roles. It’s the narrative of the political event and the analysis of it that becomes the central focus of the film.

Fatehi: So, should we consider State of Siege primarily a historical film, a mystery-crime film, or a political film?

Salamatian: As I mentioned, State of Siege is Gavras’ first film where politics and its analysis truly form the core. This is exactly the kind of political film that Gavras himself defines in a specific way. He reconstructs a political reality based on an actual event, though, in doing so, he blends elements from various characters and situations. Gavras meticulously reconstructs reality to guide the audience toward understanding the political truths behind it.

From this perspective, while State of Siege recounts a day-by-day account of events in a small country, its context is not limited to Uruguay. The film speaks to broader political transformations in Latin America over the three decades leading up to the event. It even resonates with the historical backdrop of the Vietnam War and reflects political experiences in other parts of the world, such as Iran from 1953 onward.

For example, it comments on the shift in the Truman administration’s Point Four Program, which initially aimed to advise underdeveloped countries on progress but eventually became a theoretical and operational tool for orchestrating coups. The film effectively captures this transformation.

The characters of the hostage-takers, while identified as the Tupamaros, also reflect the characteristics of various other Latin American revolutionary groups from that era. What I find most significant in Gavras’ cinematic creation is how he takes fragments of political reality to build characters and situations that can be applied universally. The conclusions he draws from these situations are, in my view, extremely important.

The film isn’t just a cinematic achievement; it’s a cohesive and well-structured narrative that distills complex historical events and presents them in a way that encourages critical engagement. Furthermore, by involving viewers in analyzing a specific period of armed struggle in Latin America and the U.S. government’s response to it, the film prompts the audience to reflect on the broader trajectory of armed struggle in the transition to democracy. It urges viewers to critically assess its effectiveness and realize that hasty and voluntarist actions rarely yield positive, long-term results.

Fatehi: We’re looking at a Gavras who comes from a communist family, has leftist leanings, but over time, we see a transformation in his films. Since you’re close friends with Gavras, where do you think this intellectual evolution came from?

Salamatian: Gavras was part of the circle surrounding Simone Signoret, the French actress and wife of Yves Montand. Signoret, who was financially comfortable, owned a chic apartment in Paris that became a major gathering place for intellectuals between 1965 and 1970. It was in these circles that a segment of French leftist artists decided to break away from the Communist Party’s influence and their unwavering loyalty to the socialist bloc. They started engaging in serious discussions about democratic values.

Now, some might dismiss Parisian intellectual salons as trivial, but they played a crucial role in shaping the political trajectories of Third World countries, from South Africa to Algeria. These spaces were freer—open to scrutinizing everything—from communism to Sartre, from the pursuit of victory to critiquing armed struggle. Everything, everyone, and every value were up for critical examination. Costa-Gavras was shaped within these intellectual circles.

Fatehi: In the final scene, we see a new American official arriving to replace Santore, and in a way, Gavras delivers his verdict—he suggests that nothing has changed, that the guerrilla actions have been ineffective. What’s your take on this?

Salamatian: The primary issue for any political activist is to disrupt the power balance against the dictatorship governing their country. Those who argue that Gavras presents a complex narrative in this film are absolutely right. He begins with a gripping sequence that pulls the audience in, holding their attention through every twist and turn, until, at the very end, he releases them as the cinema doors open.

What’s important is that Gavras doesn’t personalize the narrative. His approach is deliberate. By showing the new American diplomat arriving after the events, he makes it clear that this new official is even more professional and repressive than Santore. This isn’t by accident. From Gavras’ perspective, State of Siege isn’t a film that portrays the Tupamaros as heroes, nor is it a simple exposé of U.S. imperialism. It’s a film that looks at the logic behind armed struggles across Latin America—struggles that aimed to replace democratic, union-based activism.

Allende, who believed strongly in legal and electoral means, rejected Castro’s suggestion to form a military militia. But he did allow Gavras to make the film in Chile. Gavras, coming from both the French and Greek Communist Parties, had lost faith in the Soviet Union’s support for liberation movements. Meanwhile, another faction had emerged—after Castroism—that argued their greatest ally was the gun.

Allende said that the best ally is not the gun. Just consider this comparison—Allende, who refused to form armed guerrilla groups to defend the workers’ movement, and the narrative we’ve been told for 40 years: how, on the final day, the Tudeh Party proposed to Dr. Mosaddegh that they take up arms, but Mosaddegh refused. There are strong similarities between these two cases. What I’m saying is that this is a judgment between two approaches, and from this angle, State of Siege really lays out this dilemma. One approach is strategic, measured, and based on political persistence, aiming to change the balance of power over time. Even if it fails, it can return, but with a stronger power base.

But in Iran, after the 1953 coup, the armed guerrilla movement—what we also called militancy—emerged. The moment you criticized the use of weapons, you were labeled a traitor.

Fatehi: So, could we say that Gavras opposed armed struggle at that time?

Salamatian: Gavras has a different logic. The urgency of a protagonist’s actions doesn’t always align with the outcome of their struggle. Their haste can lead them directly into the trap of the opponent’s desired power balance. We see this in Z too. Z serves as a prelude to the colonels’ victory in Greece. I had the chance to discuss these films with Gavras between 1975-76 and again in 1982-83. It was clear that, even back then, Gavras understood these political dynamics and the direction events were taking.

Gavras said, “As a filmmaker, I took a drama and structured it in a way that preserved the essence of the event.” He views politics—and political rivalries—much like a mafia feud, a battle between traffickers, or even a love affair. That’s why he brings all the key elements involved in those conflicts into the political arena. When someone can recognize all the crucial factors of a tragedy, they develop the ability to analyze the circumstances and predict the course of power. And that prediction often carries a prophetic quality. That’s the genius of an artist. When an artist executes their craft well, they can achieve something through imagery that a political analyst might struggle to convey in dozens of pamphlets and propaganda.

But, as a politically engaged activist, I might say: “He has betrayed us.” That means, “He’s turned against the Soviet Union.”

An artist’s courage is in how they distance themselves from their political family to express the truth. Their bravery also lies in how they stand up to power. Gavras himself has said, “I didn’t make my films under the shadow of dictatorship. I made them outside that shadow.” However, to challenge the dominant global ideology of the time required great courage. Later, when Hollywood refused to support his films, he remarked in an interview, “The most powerful dictatorship I ever encountered was the dictatorship of capital in Hollywood because it had the power to decide whether a film would be made or distributed—or not.”

Art and Politics in Costa-Gavras’ Vision

State of Siege is not merely a narrative about a political crisis in Latin America; it also serves as an analytical exploration of the logic behind armed struggles and the interventions of global powers. The film delves into the motivations, objectives, and repercussions of these conflicts, shedding light on the political and social complexities of its era. Costa-Gavras’ masterful direction, combined with the nuanced political analysis provided by Ahmad Salamatian, illustrates how cinema can function as both a platform for dialogue and a critical tool for examining power structures.

Scenes such as the guerrilla interrogations and the portrayal of moral contradictions between the leftist fighters and the U.S.-backed governments offer an unflinching critique of global interventions. Through this work, Costa-Gavras demonstrates that storytelling in cinema can transcend not only geographical and political boundaries but also become a universal voice for justice. The film’s message, relevant at the time of its creation and for future generations, is deeply inspiring. It shows how cinema can be a potent force for social critique and a catalyst for change.

Cinema as Political Reflection and Critique

Cinema as Political Reflection and Critique Interview with Ahmad Salamatian on State of Siege

Interview with Ahmad Salamatian on State of Siege