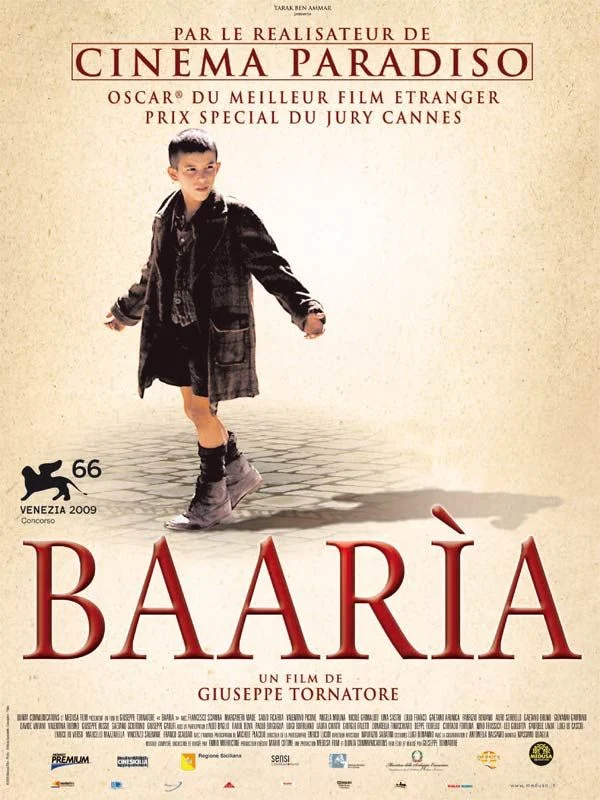

Giuseppe Tornatore’s Baarìa, his twelfth feature film, presents a lyrical and epic journey through Italy’s modern history, earning a special place at the Venice Film Festival. Much like Cinema Paradiso, Baarìa adopts a nostalgic and sentimental perspective on the past, chronicling three generations of Sicilians who navigate oppression, poverty, and war across different historical periods, ultimately shaping their political consciousness. The film’s deeply evocative atmosphere is further elevated by Ennio Morricone’s mesmerizing score. His haunting melodies enhance the film’s emotional depth, transforming it into an unforgettable cinematic experience.

The film’s title refers to a small town in Sicily—Tornatore’s birthplace—and its narrative spans from the era of fascism to the establishment of the Italian Republic. The story follows its protagonist, Peppino, from childhood, growing from a humble shepherd into a committed communist activist. Yet Baarìa is more than Peppino’s personal journey; it is a poetic meditation on Italy’s social and political evolution over the decades.

Poetry and Fragmentation in Narrative

Departing from classical cinematic storytelling, Baarìa eschews a linear structure. Instead, it unfolds as a series of scattered memories, employing flashbacks and rapid time jumps to weave its story. This approach lends the film a literary quality, bordering on the poetic. However, for viewers accustomed to cohesive, traditionally structured narratives, this fragmented style may feel intricate—or at times, even disorienting.

Tornatore masterfully uses meticulous framing, warm, vibrant lighting, and breathtaking Sicilian landscapes to craft a grand visual tapestry of rural life. The film’s meticulous set and costume design authentically immerse the audience in its historical setting. However, at times, the film’s strong emphasis on visual beauty overshadows character depth, leaving some figures underdeveloped.

One of Baarìa’s undeniable strengths is Ennio Morricone’s hauntingly evocative and emotionally profound score. As in his previous collaborations with Tornatore in Cinema Paradiso and Malèna, Morricone’s melodies play a crucial role in defining the film’s atmosphere. His delicate yet haunting compositions deepen the film’s nostalgic and dramatic essence, adding a profound emotional layer to key moments.

The performances—particularly Francesco Scianna’s portrayal of Peppino—are compelling and authentic. However, the film’s episodic structure and expansive scope leave certain characters underdeveloped. For instance, Peppino’s wife—despite her significance in his life—remains somewhat in the background, with limited space to fully reveal her motivations and inner conflicts.

Politics, Idealism, and the Struggle Against Reality

aarìa is more than just a romantic or family drama; it is a reflection of Italy’s political and social transformations in the 20th century. Giuseppe Tornatore seamlessly blends personal narrative with political history, crafting a semi-autobiographical film that chronicles Italy’s journey from fascism to the Cold War. A key theme of the film is the enduring grip of traditional power structures in Sicily, where landowners, aristocrats, and the local mafia resist societal change, viewing it as an existential threat.

This critique goes beyond historical analysis, subtly questioning the resilience of democracy in post-war Italy, where corruption and the enduring grip of old elites hinder genuine progress. The film also explores the role of populism in shaping political engagement, illustrating how political parties use grand slogans and sweeping promises to rally support. However, this surge of political enthusiasm soon unravels into factional strife and internal discord.

Street clashes and ideological rifts between communists and rival factions highlight the struggle to transform revolutionary ideals into tangible societal change. Peppino, once a fervent revolutionary, gradually adopts a more pragmatic and reformist outlook. His transformation is best captured in a poignant exchange with his son. When asked, “What is a reformist?” Peppino responds, “A reformist is someone who realizes that when you bang your head against a wall, it’s your head that breaks—not the wall.”

Peppino’s defining trait throughout the film is his defiance of tradition and established norms. His defiance is not confined to politics; it permeates his personal life as well. Even in marriage, he defies societal expectations, choosing independently rather than yielding to familial pressures—further underscoring his drive to break free from entrenched traditions.

The film’s symbolism enriches its political critique, adding layers of meaning to its social commentary. Among the film’s most striking figures is the dollar-seller in the town square, a man who shifts between selling U.S. dollars and ballpoint pens. He embodies the opportunistic lower class—constantly adapting to survive in a society where ideology and principles are frequently compromised for economic survival.

Bureaucracy emerges as another major hurdle in Italy’s post-republic transition, portrayed as a persistent barrier to progress. Despite the shift in governance, administrative corruption endures, with personal connections taking precedence over official procedures. This theme finds powerful expression in Peppino’s relentless battle against bureaucracy, as he struggles to enact change.

One of the film’s most powerful scenes contrasts personal bonds with political divisions. As Peppino marches off to join the street protests, his neighbor—a police officer—sets out at the same moment to quell those very demonstrations. Their wives stay home, anxious for their safety, yet in everyday life, the two men share a cordial bond. This moment powerfully illustrates how Mussolini’s fascist regime turned ordinary people against each other, forcing them into opposing camps despite any personal animosity. Ultimately, Baarìa examines the erosion of idealism when faced with economic and social realities. Peppino, once devoted to communist ideals, is eventually driven by financial hardship to leave Italy and seek work in France. Once a staunch opponent of capitalism, he ultimately yields to its mechanisms for survival. His transformation starkly illustrates the inevitable clash between ideology and livelihood, symbolizing the downfall of political dreams under economic pressure.

Tornatore doesn’t just articulate politics through dialogue; he weaves it into the film’s visual language and subtext. Dimly lit party meetings, flickering lights in critical moments, and the silent, watchful gazes of village elders toward revolutionaries all evoke an underlying tension—an omnipresent yet unspoken political force shaping people’s lives. This narrative approach allows Baarìa’s political messages to emerge organically, not as overt statements but as sensations woven into its atmosphere, imagery, and underlying themes.

Great Dreams in Small Hands

Baarìa, at its core, is a family drama that delicately yet profoundly reflects Italy’s political and social transformations. Though not overtly partisan, Tornatore presents modern history through the lens of ordinary people, revealing how ideologies, power, and idealism shape individual destinies.

Aesthetically, the film stands as a lasting testament to Tornatore’s poetic cinema, though its nonlinear, episodic structure may challenge some viewers. With breathtaking visuals, Ennio Morricone’s evocative score, and a deeply sentimental gaze into the past, Baarìa unfolds as a visually mesmerizing and emotionally profound experience.

In the final scene, Peppino delivers a poignant line to his son, filled with both longing and disillusionment:

“We want to embrace the world, but our hands are too small for it.”

Whether this signifies the end of Peppino’s journey or a solemn reflection on a generation’s unfulfilled dreams, it powerfully embodies Tornatore’s critique of grand ambitions forever beyond reach.