My take on the movie

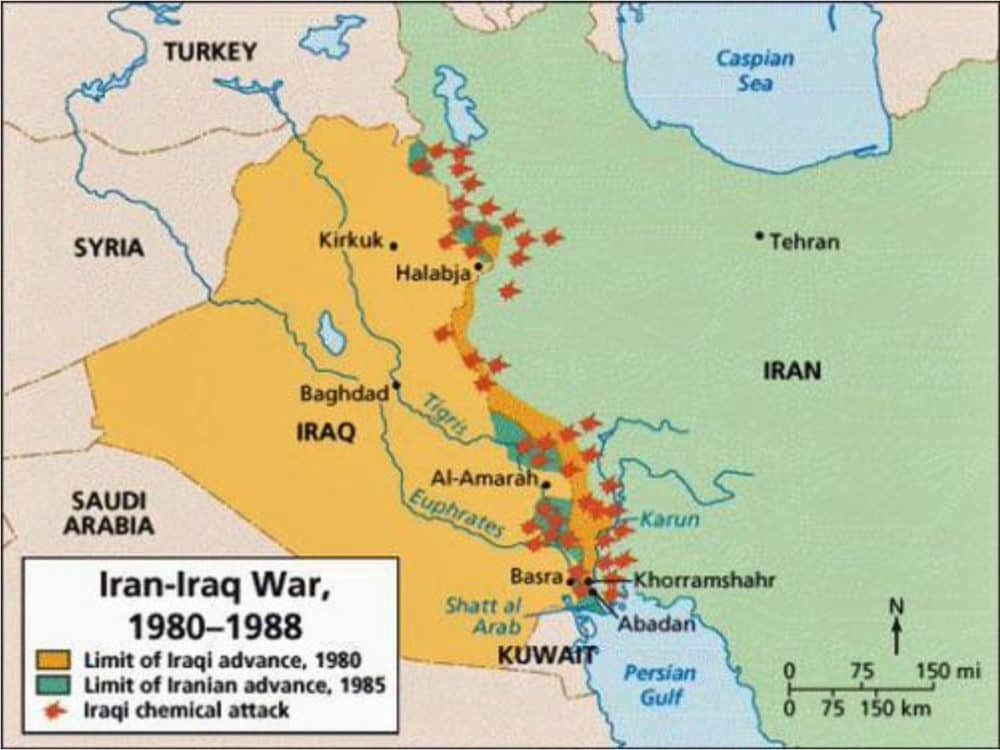

The soldier who controls the fire while perched atop a tower is the subject of this movie. He observes interpersonal interactions, the city, life, and the dead. He has the option of killing some or sparing others. It appears as though he is taking God’s seat in the chair. Decisions affecting other people’s life must now be made by the frivolous child of yesterday who used to care for the bees. We have to murder them all, he says hesitantly. If I don’t murder one, tomorrow my buddies could be killed by the same enemy soldier. If we bomb them, they will become enraged and bomb the city, and I will be held accountable for my countrymen’s deaths. Siavash is aware that his actions can prompt the enemy to launch an attack on the city. This implies that retribution is a vicious circle that never ends and that violence is the reproduction of violence. Both parties are seeking retribution.

Both the enemy’s conduct and his buddies’ behavior, as seen when he uses the other camera, are the same. Muslims are pleading and feeling compassion on both sides. Gray replaces the typical black and white of battlefronts. He distinguishes himself from the other artillery personnel because he can witness the effects of his operations. Not everyone is able to support the weight. During the movie, we shall see how other visitors to this observation point become insane.

The climax of the film comes at the end of the film, where in today’s Abadan footage we hear the voice of Siavash, who died in the footage before:

If a bee bites, it expires.

I’m not sure. Does he know that if he bites, he will perish?

If she bites, only the queen bee survives.

The bee in peril must decide whether to put her life or the security of her home first.

Separating the queen bee, immune to death even if she bites, the director separates the soldiers and the political leaders: the decision makers and the makers of wars, those who risk their lives in front of a difficult choice.

During the course of the movie’s plot, Siavash changes; he moves from scorn to doubt before regaining his composure.

In this movie, the characters’ first names are incredibly significant.

Siavash

Siavash is a beautiful, strong, and mistreated warrior whose death is a huge tragedy in Iranian literature from the past. His mythology, which dates back before Islam, continues to inspire Iranians. His name is associated with locations from Herat in Afghanistan to Shiraz (Greater Persia). The tradition states that Siavash and Rostam engage in combat when Turan [13] attacks Iran’s boundaries. He achieved enormous success. The king of Turan, Afrasiab [15], requests peace. To get the King of Iran’s approval for peace, Siavash sent a messenger to the Palace of Kavos [16], which serves as his residence. Kavos refuses to accept peace and commands Siavash to execute all prisoners! Siavash breaks away from the Iranian soldiers out of rage. He spent several years in exile before being assassinated in a plot.

Jamshid

One of the legendary rulers of Persia is named Jamshid. His name can be found in manuscripts from the Islamic era, the Avesta [17] texts, and the Pehlevi script [18]. It has a significant role in Persian mythology. He was actually an urban engineer and the one who invented the vast Iranian army. He produced a lot of weaponry, and his army was powerful. The son of Tahmures [19] and a magnificent king, Jamshid is described in the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings). After a while, he turns selfish, forfeits the Khvarenah [20], and Zahhak kills him [21]. There is no doubt that the two names chosen for the two key characters in this movie’s plot were not chosen randomly.

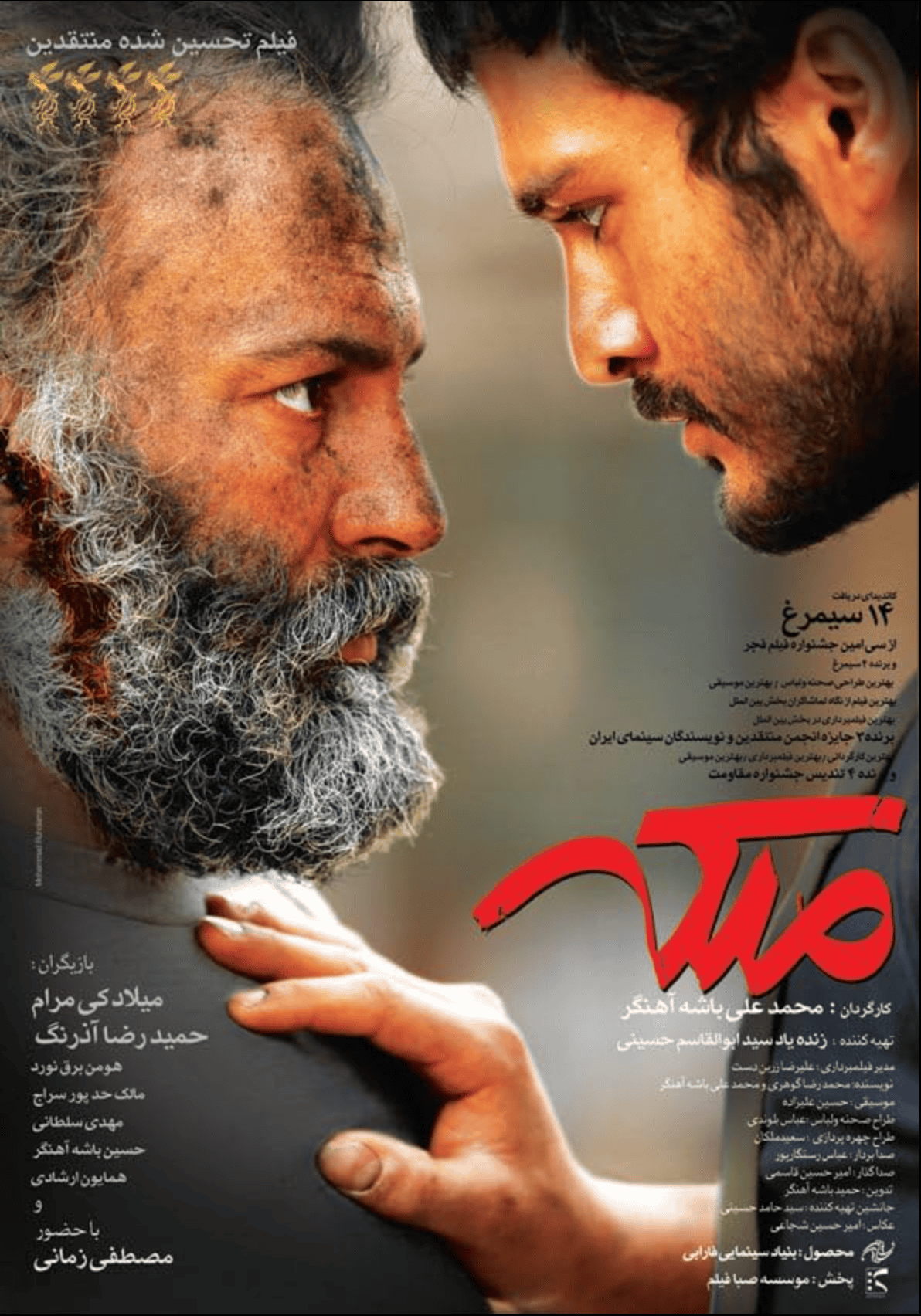

One of the most notable recent Iranian war films is The Queen (2012). This film takes a global perspective on the conflict, exploring the experiences of troops on both sides of the front. It also examines the role of leaders in causing wars and perpetuating cycles of violence and retaliation. Despite its critical acclaim, The Queen faced challenges in Iran due to its portrayal of the conflict and its political implications. Iranian conservatives and fundamentalists opposed the film’s message, which ran counter to their goals of promoting political Islam and theocracy. Nevertheless, The Queen remains a powerful and thought-provoking film that sheds light on the human cost of war and the importance of peace.

One of the most notable recent Iranian war films is The Queen (2012). This film takes a global perspective on the conflict, exploring the experiences of troops on both sides of the front. It also examines the role of leaders in causing wars and perpetuating cycles of violence and retaliation. Despite its critical acclaim, The Queen faced challenges in Iran due to its portrayal of the conflict and its political implications. Iranian conservatives and fundamentalists opposed the film’s message, which ran counter to their goals of promoting political Islam and theocracy. Nevertheless, The Queen remains a powerful and thought-provoking film that sheds light on the human cost of war and the importance of peace.