From its very inception, Iranian cinema, in only its second film, raises a question that society has yet to find a definitive answer to. “Haji Agha”, the Cinema Actor is a remarkable film not only for its progressive and unconventional structure relative to its time but also for posing a fundamental question: How should a traditional society respond to a modern phenomenon like cinema? And where do women stand in this equation?

The film’s story revolves around a director struggling to find a fresh subject for his new film. Among his institute’s students are a young man and his fiancée. The young man suggests that “Haji Agha”, his fiancée’s father, who is staunchly opposed to cinema and theater, could serve as an interesting subject. The director welcomes the idea and lures Haji Agha to his film institute, secretly recording his movements and reactions. Later, he screens the footage for “Haji Agha” himself. Ultimately, the once-fierce opponent of cinema becomes intrigued and consents to his daughter and son-in-law continuing their careers in the film industry. Although “Ovanes Ohanian” raised this question in 1933 and provided an answer to it, the truth is that this challenge remains unresolved. Even today, decades later, many families still oppose their children’s involvement in the film industry.

The film’s story revolves around a director struggling to find a fresh subject for his new film. Among his institute’s students are a young man and his fiancée. The young man suggests that “Haji Agha”, his fiancée’s father, who is staunchly opposed to cinema and theater, could serve as an interesting subject. The director welcomes the idea and lures Haji Agha to his film institute, secretly recording his movements and reactions. Later, he screens the footage for “Haji Agha” himself. Ultimately, the once-fierce opponent of cinema becomes intrigued and consents to his daughter and son-in-law continuing their careers in the film industry. Although “Ovanes Ohanian” raised this question in 1933 and provided an answer to it, the truth is that this challenge remains unresolved. Even today, decades later, many families still oppose their children’s involvement in the film industry.

1950s-1960s: Women in Iranian Cinema – Stereotypical Depictions and Lack of Individuality

The 1950s can be considered a period in which women in Iranian cinema were not portrayed as independent characters but rather as tools to attract audiences and ensure box office success. During this era, female characters lacked individuality and were confined to repetitive and stereotypical roles. Filmmakers paid little attention to acting skills when selecting actresses and instead sought faces that were already famous in other fields, particularly music. The presence of female singers in cinema, who were widely popular among the public, not only boosted film sales but also enhanced their own fame. This reciprocal relationship between cinema and music reinforced the trend of such casting choices in films of that period.

The roles assigned to women in these decades were primarily limited to characters such as singers, maids, or dancers. In most films, women were either beautiful and seductive mistresses serving the male-driven narrative or innocent and passive girls who ultimately surrendered to their circumstances. Independent and influential female characters had little to no place in Iranian cinema at the time. Rather than reflecting social realities, films of this period reinforced gender stereotypes. This perspective not only shaped cinema but also influenced the broader culture, ensuring that women’s roles in films remained confined to these patterns for years to come.

The commercial approach dominating cinema at the time played a significant role in perpetuating this image of women. Film producers and investors prioritized profitability over storytelling and content quality, relying heavily on well-known figures from the music and theater industries to achieve this goal. Female singers, who had a large fan base at the time, became the ideal choice for this strategy. Their presence in films not only guaranteed the movie’s popularity but also amplified their own fame. As a result, many films effectively turned into visual clips promoting these figures, with acting and narrative storytelling taking a backseat.

By the 1960s, Iranian cinema gradually began to feel the impact of competition with foreign films. The middle class, in search of higher-quality productions and better standards, largely preferred foreign films, whereas the primary audience for Iranian cinema remained the lower-income segments of society. This shift in audience composition pushed Iranian films toward specific formulas primarily aimed at attracting attention and maximizing ticket sales. Consequently, cinema increasingly adopted a cabaret-style structure, where female leads were chosen not based on acting skills but on their abilities in dancing, singing, and physical appeal.

Iranian cinema in the 1950s and 1960s confined women’s roles within narrow, stereotypical frameworks and erased their individuality from cinematic narratives. This perspective was not only a reflection of the social conditions of the time but also actively contributed to shaping a degrading image of women in public culture. Although later decades—especially with the emergence of New Wave cinema—saw efforts to challenge this status quo, the deep-rooted effects of this period lingered in Iranian cinema for a long time. Even today, traces of this perspective can still be seen in certain contemporary productions, where women remain marginalized within cinematic narratives.

During this period, Iranian cinema became largely fixated on the objectification of women. More than ever, the presence of women in films was reduced to the display of their bodies and sexual appeal. Filmmakers, eager to boost sales and attract audiences, confined female characters to shallow and stereotypical roles. In many films, women were either cast as the “seductive and alluring” figure or the “innocent and victimized” woman, whose only salvation lay in a male hero—typically portrayed as a chivalrous and streetwise character. This narrative formula relegated women to the margins, making them dependent on strong male saviors within the story.

This marginalization was not limited to film narratives but extended behind the scenes as well. In the cinema of the 1960s, women were not only sidelined in storytelling but also in the industry itself. The number of female screenwriters, directors, or producers was nearly negligible, and decision-making in the film industry remained firmly in the hands of men. The prevailing perspective viewed women not as fully realized characters but as visual elements meant to enhance a film’s appeal. This trend resulted in the mass production of superficial and commercial films in which women were primarily used as tools for attracting audiences.

1970s: The Beginning of Transformation in Iranian Cinema and the Decline of the Cabaret Woman

The 1970s marked a flourishing era for the arts in Iran, and cinema was no exception. The Iranian New Wave, which had been ignited in the late 1960s with films like Gheysar and The Cow, fully emerged during this decade. This transformation reshaped the narrative structure of films, leading to the elimination of the cabaret woman—one of the dominant stereotypes in Iranian cinema up to that point. No longer was a pleasant singing voice or an attractive appearance enough to sustain a career in film; acting ability became a serious criterion.

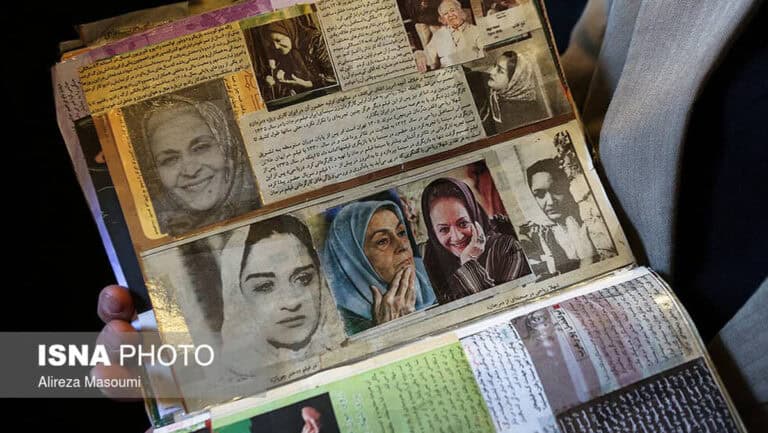

Actresses such as Pouri Banai, Forouzan, Farzaneh Taidi, and Googoosh, who possessed both fame and acting talent, adapted to this new cinematic wave. Meanwhile, others, like Soraya Beheshti, faded from the industry. This shift, though seemingly natural at first glance, was striking in the case of Beheshti, who had appeared in over 40 films before the New Wave took hold. Iranian cinema during this period placed greater emphasis on acting skills than ever before, setting new standards for women’s participation in the film industry. Some believe that the disappearance of many female actors from Iranian cinema was a direct result of the 1979 Revolution, but this claim is not entirely accurate. Fundamental changes in cinema had already begun before the revolution with the emergence of the New Wave. What has been less discussed, however, is the role of women behind the camera. Up to this point in Iranian cinema history, there were virtually no female filmmakers, with only two notable exceptions: Shahla Riahi and Forough Farrokhzad. Shahla Riahi directed Marjan in 1956, with the support of her husband, who was a film producer. Although the film followed a simple narrative similar to those found in tabloid magazines, it was significant in two key ways. First, it was the first film in Iranian cinema history to be directed by a woman. Second, unlike the mainstream cinema of the time, it lacked the typical dance and musical sequences. Riahi attempted to create a straightforward melodrama that diverged from the common cinematic formulas, but audiences, accustomed to conventional stereotypes, did not embrace it. In an attempt to recover from the financial loss, dance and musical scenes were later added to the film, yet even these changes could not prevent its commercial failure. The male-dominated film industry, which remained deeply attached to its established norms, did not allow this film to succeed.

Actresses such as Pouri Banai, Forouzan, Farzaneh Taidi, and Googoosh, who possessed both fame and acting talent, adapted to this new cinematic wave. Meanwhile, others, like Soraya Beheshti, faded from the industry. This shift, though seemingly natural at first glance, was striking in the case of Beheshti, who had appeared in over 40 films before the New Wave took hold. Iranian cinema during this period placed greater emphasis on acting skills than ever before, setting new standards for women’s participation in the film industry. Some believe that the disappearance of many female actors from Iranian cinema was a direct result of the 1979 Revolution, but this claim is not entirely accurate. Fundamental changes in cinema had already begun before the revolution with the emergence of the New Wave. What has been less discussed, however, is the role of women behind the camera. Up to this point in Iranian cinema history, there were virtually no female filmmakers, with only two notable exceptions: Shahla Riahi and Forough Farrokhzad. Shahla Riahi directed Marjan in 1956, with the support of her husband, who was a film producer. Although the film followed a simple narrative similar to those found in tabloid magazines, it was significant in two key ways. First, it was the first film in Iranian cinema history to be directed by a woman. Second, unlike the mainstream cinema of the time, it lacked the typical dance and musical sequences. Riahi attempted to create a straightforward melodrama that diverged from the common cinematic formulas, but audiences, accustomed to conventional stereotypes, did not embrace it. In an attempt to recover from the financial loss, dance and musical scenes were later added to the film, yet even these changes could not prevent its commercial failure. The male-dominated film industry, which remained deeply attached to its established norms, did not allow this film to succeed.

Around the same time, Forough Farrokhzad directed the documentary The House is Black. Although the film was not specifically about women—it focused on the lives of leprosy patients in Tabriz—its distinct and feminine perspective secured a unique place in the history of Iranian cinema. At a time when nearly all films were made from a male point of view, this documentary stood as a rare example of an alternative, deeply personal vision. However, the film was never given a theatrical release and, like many independent works, remained largely unseen by audiences.

Overall, in the three decades preceding the New Wave, the portrayal of women in Iranian cinema was reduced to weak, naïve, and deceived figures, bearing little connection to social realities. During these years, no feminist movement emerged within Iranian cinema, and narratives remained tools for reinforcing gender stereotypes. Perhaps the most striking example of how women were depicted in the patriarchal pre-revolutionary cinema can be found in a famous scene:

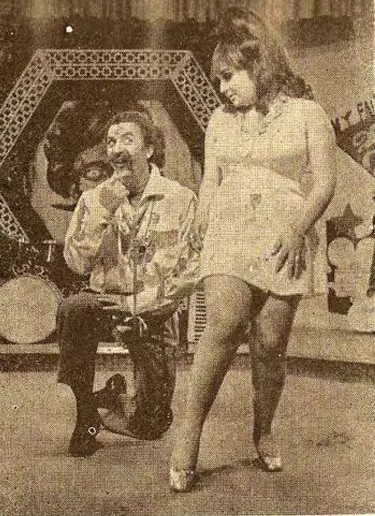

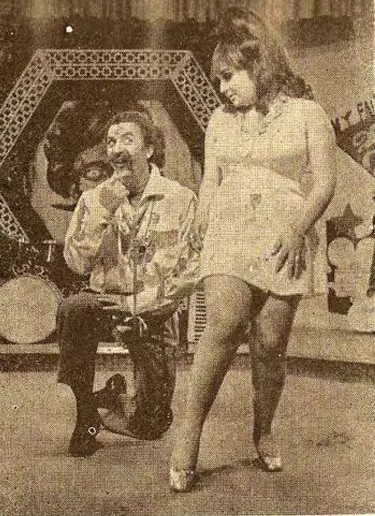

The male protagonist sits in a cabaret while a woman named Nazi dances and sings on stage:

Throughout this scene, as Nazi seductively dances and performs, the camera repeatedly focuses on her lips, chest, hips, and legs. The intense gaze of the male protagonist, his subordinates, and ultimately, the film’s audience is directed by the camera’s movements, conditioning them to view the woman as an object of pleasure.

Ultimately, women in pre-revolutionary Iranian cinema were reduced to two dominant archetypes:

- The Virtuous Woman: The elderly mother, the modest sister, or the dutiful housewife—figures who represented the ideal and acceptable model of womanhood in society.

- The Corrupt Cabaret Woman: A woman whose redemption was only possible through the intervention of the male hero, who would ultimately “cleanse” her and transform her into a submissive and virtuous figure.

Of course, this critique does not apply to New Wave films, as this movement successfully challenged many of the past stereotypes. However, when examining the dominant trend in Iranian cinema before the revolution, it is clear that women remained marginalized—both in narratives and behind the scenes. Cinema did not serve as a true reflection of their social realities.

The 1979 Revolution and Post-Revolutionary Cinema: Between New Opportunities and Ideological Instrumentalization

Like any major social movement, the 1979 Revolution not only brought sweeping changes but also introduced new forces into the social landscape. Women, who had actively participated in the revolution, reached a level of awareness that led them to recognize their right to an independent position in various fields, including cinema. Before the revolution, for religious families, allowing women to enter the film industry seemed unthinkable. However, with the Islamic government legitimizing and strictly controlling cinema, a new avenue opened—one that allowed women from religious and traditional backgrounds to step into the industry.

The Islamic government’s presence in the cultural and artistic sphere reshaped Iranian cinema. Religious groups that had previously viewed cinema as a corrupt and immoral space now granted it legitimacy, as it was aligned with the values of the new Islamic state. Many religious families, who once forbade their daughters from entering the industry, no longer saw a reason to object, given the implementation of Islamic laws and oversight. While these changes imposed significant restrictions on cinematic content, they simultaneously opened doors for a segment of women who had previously been denied entry into the industry.

The author does not deny the widespread exclusion of prominent filmmakers during this period but highlights the fact that these transformations also created opportunities for a different group. This duality is characteristic of deep social shifts: while some are pushed aside, others find new paths to enter.

Post-Revolutionary Cinema: From the Erasure of Women to the Emergence of Female Filmmakers

After the revolution, Iranian cinema underwent profound transformations, which can be divided into three main phases.

In the first phase, during the era of revolutionary and war cinema, the depiction of women in films changed drastically. In contrast to pre-revolutionary cinema, which had turned women into tools for visual and commercial appeal, revolutionary cinema sought to minimize their presence as much as possible. Many films of this period either had no female characters at all or featured women so marginally that they were barely visible. When women did appear, great effort was made to strip them of any feminine allure. This was, in essence, a radical reaction against the exaggerated portrayal of women in pre-revolutionary cinema. However, the outcome still reinforced patriarchy, as women were either absent or relegated to the background.

As the fervor of the revolution and war subsided, the second phase saw the rise of melodrama as one of Iranian cinema’s most popular genres. Melodrama, by nature, required the presence of women, making their return to the screen inevitable. Consequently, films centered around female protagonists began to emerge once again. Though this reappearance remained confined within the ideological and regulatory framework of the Islamic government, it nevertheless signaled a gradual shift in the status of women in cinema.

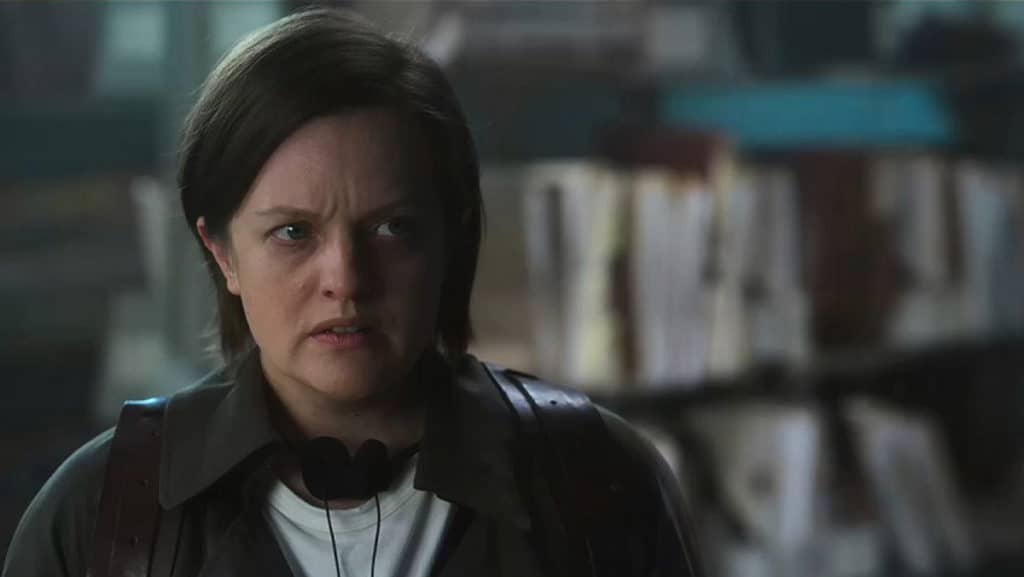

The third phase, marked by the arrival of female filmmakers, was a turning point in the history of Iranian cinema. During this period, women not only appeared in front of the camera but also stepped behind it, directing and producing their own films. This development brought about two fundamental changes: first, it introduced a distinctly female perspective into cinema, and second, it led to a more serious exploration of women’s issues on screen. This transformation impacted not only women’s cinema but also influenced male filmmakers, prompting them to engage with social issues affecting women.

The peak of this movement can be seen in Offside by Jafar Panahi, a film that directly addressed one of the most significant protests by women in Iranian society—their exclusion from stadiums.

These shifts even led to a transformation in the cinematic approach of some male directors. A notable example is Ebrahim Hatamikia, a filmmaker who in his early works completely omitted female actors. However, over time, he directed Invitation (Da’vat), which is arguably the most female-centered film ever made by a male director in Iran.

Three Golden Decades of Female Filmmakers in Iran

The third phase of women’s entry into Iranian cinema can be divided into three key stages, each playing a crucial role in the growth and consolidation of female filmmakers.

The 1980s: The First Female Filmmakers of Post-Revolutionary Iran

In the 1980s, the first generation of female filmmakers emerged after the revolution. Pouran Derakhshandeh became the first female director of the post-revolution era, debuting in 1986 with Rabeté (The Relationship). Just a year later, she made history by winning the Crystal Simorgh at the Fajr Film Festival for Parandé-ye Kuchak-e Khoshbakhti (The Little Bird of Happiness).

Rakhshan Bani-Etemad, who had been working in television before the revolution, entered cinema in 1987 with Kharej az Mahdudeh (Out of Range), becoming Derakhshandeh’s only serious female rival at the time. During the same decade, Marzieh Boroumand, who had gained recognition in television, made a successful transition to cinema with the widely popular Shahr-e Mooshha (The City of Mice).

The fourth major female filmmaker of this era was Tahmineh Milani, who entered the industry with Bacheha-ye Talagh (Children of Divorce).

A defining characteristic of this generation of female directors was their prior experience in cinema or television before or immediately after the revolution. Their films primarily focused on social themes, centering on issues related to women and family dynamics.

The 1990s provided a fertile ground for the emergence of new names in Iranian cinema. Yasmin Maleknasr entered the industry in 1994 with Dard-e Moshtarak (The Common Pain). Maryam Shahriar gained recognition as a fresh voice with Dokhtaran-e Khorshid (Daughters of the Sun), while Manijeh Hekmat first established herself as a producer before stepping into directing.

One of the most significant female filmmakers of this decade was Samira Makhmalbaf, who became one of the most prominent directors of Iran’s second cinematic generation. With The Apple (Sib), she made her way into international festivals and ultimately won the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

At the close of the decade, Marzieh Meshkini joined this movement with Roozi ke Zan Shodam (The Day I Became a Woman) in 2000, further solidifying the presence of women in Iranian film directing.

The 2000s marked the peak of women’s participation and advancement in Iranian cinema. The number of female filmmakers increased to an unprecedented level, something unimaginable just a decade earlier. Directors such as Ansieh Shah-Hosseini, Niki Karimi, Mona Zandi-Haqiqi, Hana Makhmalbaf, Shirin Neshat, Marjane Satrapi, Parisa Bakhtavar, and Granaz Moussavi—among many others—entered the industry, offering fresh perspectives on women’s issues and broader societal concerns. Each film directed by these women delved deeper into gender-related themes, challenging social norms and expanding the visibility of women in public life.

A particularly notable aspect of this period is the role of cinema as one of the most widely accepted mediums for engaging with Iran’s predominantly oral society. Iranian cinema played a crucial role in highlighting social concerns and initiating public discourse. Among various studies on this phenomenon, a report published by the Parvin E’tesami Film Festival provides a striking statistic: 800 female filmmakers registered to participate in the festival. This figure—which includes documentary, short, and feature-length filmmakers—demonstrates a remarkable increase compared to the small handful of female directors in previous decades. It stands as undeniable evidence of the significant rise in women’s presence within Iranian cinema.

Collectively, these three decades represent a significant turning point in the history of Iranian cinema. From the emergence of the first female filmmakers after the revolution to the consolidation of their presence in the 1990s, and finally, the widespread wave of women entering the film industry in the 2000s, this period reflects a gradual yet profound transformation in the role of women in Iranian cinema. This evolution not only reshaped the narratives presented on screen but also redefined women’s position both in front of and behind the camera, marking an undeniable shift in the industry’s landscape.

How can the relationship between the Islamic government and cinema be defined? The Islamic Republic has consistently sought to turn cinema into a tool serving its official ideology. Post-revolutionary Iranian cinema has, for the most part, functioned less as a space for artistic creativity and more as a medium for promoting the state’s official discourse. Within this framework, the government does not seek independent artists but rather filmmakers who align with its policies and narratives.

As a result, the state has little tolerance for the voices of independent women, as its ideal model of womanhood is one that is dependent and aligned with the official ideological framework. In such an environment, cinema—like other cultural instruments—functions as a mechanism for reinforcing government-approved stereotypes, particularly those that confine women’s roles within predefined boundaries.

While the influence of hardline factions initially acted as a barrier to women’s entry into cinema in the early post-revolution years, the government eventually did not outright oppose their presence. However, what the state seeks is not the exclusion of women from cinema but rather the regulation and control of their representation. Within this framework, female characters in cinema must conform to predefined roles: the self-sacrificing mother devoted to her family, the woman who strictly adheres to state-sanctioned hijab norms, and a character whose identity is validated only in relation to the government’s values. Women who fit these molds are not only allowed to work in cinema but are often supported and celebrated.

The real challenge emerges when a woman steps outside this framework—as a filmmaker. The “female filmmaker” inherently transcends the government’s prescribed model, as her presence as a creator of cinematic works disrupts the state’s carefully constructed stereotypes. For this reason, independent female filmmakers are not only ignored but also subjected to various restrictions and pressures. Despite these challenges, the steady rise of women filmmakers and their growing success on the international stage indicate that this transformation, however difficult, is irreversible.